Welcome to the Everyone's Investment Guide. As you begin, you might want to keep in mind the new reality that Christopher L. Jones identifies in his book, The Intelligent Portfolio:

"Over the last few decades, there has been a profound shift in investment responsibility — away from professional institutions that traditionally manage financial assets and right into your lap. Today, tens of millions of people are faced with making personal investment decisions that will have a big impact on their future quality of life — but only a few feel like they know what they are doing."

The goal of this presentation is to provide essential information that will help you make sound and appropriate choices as you invest for your future.

Everyone's Investment Guide is divided into six distinct sections.

The presentation begins by answering the question "Why Invest?" and goes on to explain how to invest and the core principles that underlie investment decisions, with a focus on investing for retirement. It wraps up with a caution to be on your guard against investment scams.

You can work through the Everyone's Investment Guide from start to finish, focus on one section at a time, or move from section to section to find the information you're looking for.

Why is investing so important to meeting your long-term goals, and especially to enjoying a comfortable retirement? The fact is, the world is changing, and people must take increasing responsibility for their own financial future.

Private pensions traditionally provided by employers continue to disappear. Public pension funds are continually being squeezed by the budget pressures facing states and municipalities. In place of pensions, companies and governments are substituting employer-sponsored retirement plans, which leave many investment decisions up to the individual employees.

While employers must provide basic information about the plan and the investment options you have, it's up to you to choose among them. To make smart decisions, it's important to understand how the investments work, their potential risks and return, what they cost to buy and own, and how making different choices can affect your overall financial security.

In fact, only through informed investing is it possible to accumulate enough savings to afford a secure retirement. Long-term investors who watch their costs, allocate their assets, and diversify their portfolios tend to accumulate savings despite the ups and downs of the markets. But investors who are lured into an investment scam are likely to see their money, or a big chunk of it, disappear forever.

This presentation is designed to empower you to be a more confident, informed, and effective investor.

There are three strong reasons to invest.

- As an investor, you can meet your financial goals, such as buying a home, sending children to college, starting your own business after you retire, helping others, expanding your horizons with travel or more education, or whatever is important to you.

- Your most important goal is enjoying a secure retirement. You help make that possible by investing regularly. That way, you build up the savings you need to help cover your expenses so you can enjoy life's pleasures.

- Investing also helps provide financial security for your family, and for the people and organizations that depend on your generosity.

You can get started by reviewing some investing basics.

The $1 you have in your pocket today is worth more than the same $1 will be tomorrow or next week. That's what people mean when they talk about the time value of money: The more time that goes by, the less value your money has.

Money loses value — and buying power — as a result of inflation. To use one small example, inflation explains why a cream pie at the legendary Frisco Shop (Night Hawk) restaurant in Austin that cost 30 cents in 1959 costs $4.25 in 2012 (it's worth it). Almost anything you buy now costs more than it once did — and more than you expect it to. If you're investing to meet your goals and increase your financial security, you can't ignore inflation. In fact, you have to plan for it.

Inflation is a big part of reason it will cost you more to live in the future than it costs you now. What makes things worse is that the average inflation rate as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) has risen much faster than the average disposable personal income (DPI). Take a look at this chart comparing the CPI and the DPI over the last 30 years to see how much buying power you have lost.

So what's the solution? You'll need a source of investment income in the future that will outpace inflation and close the gap between what things will cost and what you have to spend. That will help make it possible to live at least as comfortably then as you do now.

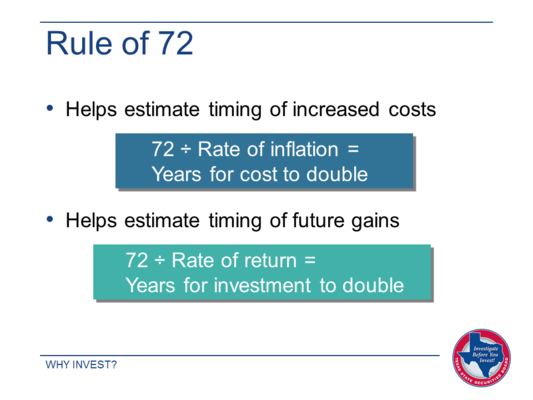

If you're wondering how much damage inflation could do to your income over the next 15 or 20 years, the Amazing Rule of 72 is a handy tool. Here's how it works: You divide 72 by the annualized inflation rate, which has been 3% since 1926. Since 72 ÷ 3 = 24, you can expect your living expenses to double every 24 years.

There's nothing unusual about a 24-year retirement, so you can see why it's critical to have more income, not less, as time goes by. Keep in mind, too, that in some years inflation is higher than 3%. Say it jumped to 6% or even 10%, which has happened in the past and could happen again. You can use this calculator to see how quickly prices would double at different inflation rates.

What's really amazing about the Amazing Rule of 72 is that it's also a quick and accurate way to estimate how quickly the money you invest will double in value.

For example, if your investment portfolio provided a 6% annualized rate of return, you could expect your account to be worth twice what you invested after 12 years (72 ÷ 6 = 12). That's even if you don't invest another cent — though ideally you would continue to add money to your portfolio every year. You can use the same calculator to experiment with the results that other rates of return could provide.

One word of caution, though: No rate of return is guaranteed, so an estimate is not a promise.

If you can double the value of your investment portfolio more quickly than prices rise because of inflation, you'll increase your net worth and be more financially secure in the future. To achieve these goals, you have to invest for growth, or an annualized rate of return that is higher than the annualized rate of inflation.

Investing for growth is different from putting your money in certificates of deposit (CDs). With CDs, your money is safe because deposits are federally insured and the return is guaranteed. The rate of return, however, is lower than the rate of inflation. In fact, these days CD returns are about as low as they have ever been and are significantly lower than the rate of inflation. Except for the federal deposit insurance, you'd probably make out as well by putting your money under your mattress!

The key to growing your investment portfolio is to start right now. The sooner you begin, the more time your money has to double — and then double again. But the longer you wait, the less growth potential you'll have.

Just as the $1 you have today is worth more than the same $1 tomorrow, so the $1 you invest today has greater potential for growth than the $1 you invest tomorrow — or next month or next year.

If you'd like to know more about how investments increase in value, you can read about compounding.

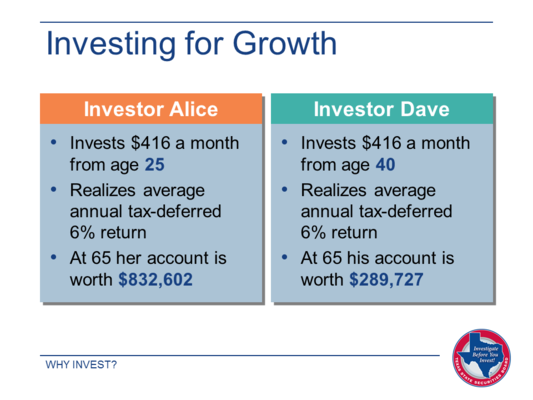

Alice and Dave are a good example of what we've been stressing — the time value of money. When Alice was 25, she started to build a tax-deferred retirement account. Dave waited until he was 40.

Alice and Dave each invested $416 a month, or about $14 a day. Both realized an annualized 6% rate of return on their investment accounts.

But look at the difference that 15 years made. When Dave turned 65, he had accumulated $289,727. But at 65, Alice's account was worth $832,602 — almost three times as much.

That's not all. Even if Alice had stopped putting money into her account when she turned 35 — after just 10 years — and she maintained an annualized 6% return, she would have accumulated $412, 637 on her $49,760 investment. So she'd still have more in her account than Dave, even though he invested $124,800 over 25 years.

The great playwright George Bernard Shaw observed, "Youth is wasted on the young." But you can prove him wrong by starting to invest as soon as you start earning and benefiting from the power of compounding. With compounding, you earn a return not only on the amount you invest but on the earnings you accumulate on your earnings.

You can see the power of compounding for yourself by using this calculator.

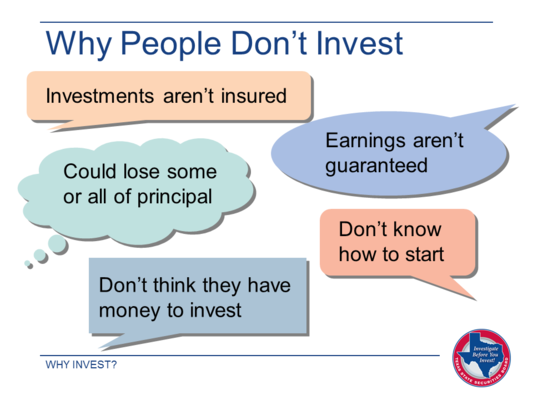

The arguments against investing are valid — to a point.

- Most investments are not insured. This means you could lose some or even the entire amount you invest.

- Investment earnings aren't guaranteed; in fact, in some periods you may have no earnings at all.

The counterargument is that over extended periods of time investments have provided a much stronger rate of return, and much greater protection against inflation than insured investments such as CDs and money market accounts or government backed Treasury bills.

For example, between 1926 and the end of 2012, the compound annual growth rate was 9.8% for large company stocks, 5.7% for long-term government bonds, and just 3.5% for US Treasury bills. Of course, what happened in the past doesn’t predict how closely your returns will come to those figures. But when you have the potential for a rate of return that’s higher than the rate of inflation, you may decide it’s worth trying.

Even with the potential, though not guaranteed, upside to investing, some people are understandably concerned that they don't know how or where to start investing or simply don't have enough money. The best remedy is to learn more about investing and how it works, which is what this presentation is designed to help you do.

You may have heard the stock market compared to a casino or investing dismissed as just another form of gambling. Those comparisons may seem legitimate at times, particularly when the volatility in the markets gives you that funny feeling in your stomach (and it's not love or the leftovers you had for dinner).

However, there are important differences between investing and gambling:

- While long-term investors who made smart investments have profited over time, long-time gamblers rarely break even and the casinos profit

- Investors manage the long-term risks of investing with strategies like asset allocation and diversification, while gamblers try to outsmart each other and the house

- The longer investors remain in the market, the greater their potential for long term gains, but the more frequently people gamble, the greater their potential for losses

- Investment returns depend on taking calculated risks over the long term, while gambling returns depend on taking major short-term risks

In other words, putting your money in the markets is a far cry from placing a bet on the roulette wheel or the blackjack table.

What's essential to successful investing is understanding how different types of investments work and which ones are appropriate for you. Often the most effective way to invest is to work with an experienced and credentialed professional who will provide the guidance you need. But there's no substitute for knowing investing basics yourself, even when you work with a professional, so you can make or participate in informed decisions.

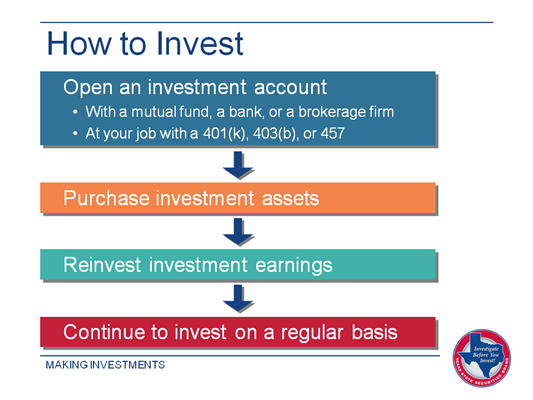

When you're ready to invest, you have to make it happen. Contrary to what you may think, it's not that complicated. In fact, it may be easier than picking a wireless phone plan. But it will take some time and requires some decisions on your part.

Step one is opening an account through which you'll purchase your investments. Banks, brokerage firms, and mutual fund companies offer a variety of investment accounts. Corporations and other businesses offer 401(k) plans, public sector organizations offer 457 plans, and school districts and other nonprofit organizations offer 403(b) plans. You decide which account or accounts to open and where to open them based on the types of investments you want to make and the goals you're investing to meet.

Step two is choosing investments. Since there are so many investment options, this may be your greatest challenge. But you can start slowly, perhaps by opening a mutual fund account and choosing a single fund such as a balanced fund or a target date fund, and broadening your investment base from there. Mutual funds, in fact, are the most common investment vehicle for most investors. The basics of mutual funds are explained later in this section.

Step three — reinvesting — is the easiest. As your investments provide earnings, you use that income to buy additional investments instead of spending it. These new investments help build your account value. And since you can often reinvest automatically, you won't miss the money you don't see.

The final step is continuing to invest on a regular basis, contributing new money to your account every month or quarter. It doesn't have to be a large amount, but recurring cash infusions can mean the difference between reaching your goals and coming up short.

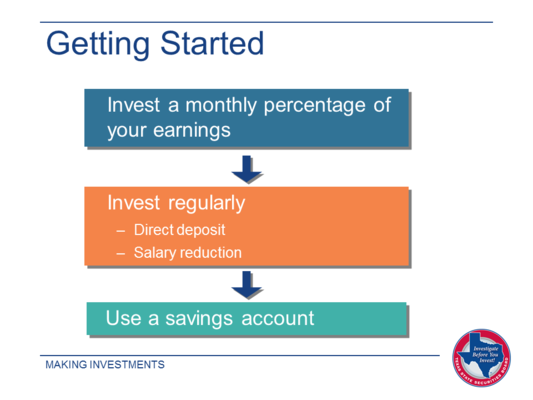

A good rule of thumb is that you should be investing 10% to 15% of your gross earnings — and perhaps more as you get closer to retirement age. Investing more may be possible, for example, if your mortgage is paid off and you're no longer paying for your children's education. On the other hand, if 10% seems too high a percentage to invest, you can always start with 5%.

What's even more important than the percentage you invest is sticking to your plan and investing regularly. One of the easiest and most effective ways to do that is by arranging for direct deposit from your paycheck, bank, or credit union account directly into your brokerage or mutual fund account. That way, you won't forget and you won't be tempted to spend the money.

If you're investing in an employer-sponsored plan that's available through your job, you defer a percentage of your salary each pay period, reducing your take-home pay but also your taxable income. This approach is not only painless, but it also postpones what you owe the IRS on the amount you defer until you begin taking money out of your account, usually after you retire.

Regular investing also means you're taking advantage of dollar cost averaging. To learn more about this long-term investment strategy and how it works, check out this interactive example.

Don't let the fact that the universe of investments is enormous intimidate you. Every investment belongs to what's known as an asset class — a group of investments that have several important features in common.

Most investors — you included — can focus on just four of these asset classes: equities, fixed income. cash equivalents, and real estate. They're described in detail in the next few pages.

What you need to know first is that each asset class puts your investment dollars to work in a different way, exposes you to different types of risk, and reacts differently to what's happening in the financial marketplace and the economy in general. For example, in a year when equities are increasing in value, fixed-income may be flat or even losing value, or the other way around.

Of course, in some periods, several asset classes do well. For example, in 2010, equities and fixed income investments both had a positive real return, but cash equivalents, measured by the return on US Treasury bills, lost value. So did real estate.

Occasionally, there is a year or two like 2008, when equities dropped dramatically in value and many investors suffered major losses, even though fixed income investments had a positive return.

There's one more important point: each asset class can be subdivided into smaller groups, or subclasses, of investments that share certain characteristics that differentiate them from the other investments in the class. You'll see shortly why that's important.

When you make an equity investment, you buy shares of stock in an individual corporation or shares in mutual funds or exchange traded funds (ETFs) that own stock in a number of corporations.

There are two ways to make money with equity investments. If the share price increases, you can sell your investment for more than you paid for it. Or you can keep the shares, increasing the value of your portfolio.

You may also be entitled to share in a company's or fund's profits. A corporation has the right to decide whether to pay a dividend, or a share of the money it makes. But a mutual fund must pass along to its shareholders the income it earns from its investments and the profits it makes from selling its holdings, after fees and expenses.

The risk with equity investments is that the prices may be volatile, and neither their market price nor the income they may provide is guaranteed. This means you could lose some or all of the money you invest if a price dropped suddenly and you sold.

Stocks and stock funds can be divided into subclasses by market capitalization, by market sector, and by the country in which their headquarters are located. Equities in different subclasses expose you to different risks and have different return potential. You can read more about these subclasses and the impact size and sector on equity performance.

You might also be interested in some expert guidance on what stock investors need to know about managing their expectations.

When you make a fixed income investment, you lend money to the corporation, government, or government agency that issues the loan. The issuer promises to repay the principal, plus interest, which is calculated as a percentage of the principal, over the term of the loan.

Profit on a fixed income investment includes the interest you earn and perhaps a capital gain if you can sell the investment at a profit. This may happen if the interest rate being paid by newer bonds is lower than the rate on the bond you own. In that case, other investors may be willing to pay more than par, or the face value of your bond, because they will earn more interest. The opposite is true if the interest rate on newer bonds is higher than the rate your bond pays: Then if you sell, you may have to settle for less than par.

You can learn more about the variety of individual bonds and how they might fit into your portfolio.

You can also buy mutual funds or ETFs that invest in individual fixed-income securities. However, these funds are actually equity investments in which you own shares rather than fixed-income investments. A bond fund doesn't pay a fixed rate of interest or promise the return of your principal, though its performance, and your income and potential profit or loss, reflects the collective performance of the bonds it owns.

To expand your bond knowledge, take a look at Bonds and Beyond.

Cash is the money you have in your pocket and your checking and savings account. Cash equivalents, on the other hand, are investments that are actually very short-term loans.

The investments that fit into this asset class include bank CDs — which actually may have terms of up to five years — US Treasury bills, and money market mutual funds. These investments have almost as much liquidity as a checking account, but provide potential earnings.

Your earnings on a cash equivalent is the interest it pays, generally calculated at a rate that's lower than that of fixed income investments. However, if the rate is very low—as it has been for the past several years — then your real return will be lower than the rate of inflation. This means your cash equivalent investment could actually lose rather than gain value over a several-year period even though the interest is added to your principal to increase its value.

On the other hand, cash equivalents expose you to limited investment risk. Bank CDs are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) if the institution issuing the CD has federal deposit insurance. US Treasury bills are backed by the full faith and credit of the US government. Money market funds invest to maintain their value at $1 per share but are usually not guaranteed. That's an important way they differ from a bank money market account, which is FDIC insured. Please make sure the institution issuing the CD has federal deposit insurance.

There's more information on cash equivalents and the part they play in an investment portfolio in this essay.

To invest in real estate, you can buy shares in a real estate investment trust (REIT) that owns commercial properties, mortgages on commercial properties, or both rentable properties and mortgages.

For example, a REIT might own shopping malls, office buildings, hospitals, warehouses, or other real estate. The more varied a REIT's properties are, either by type or geography, the greater the protection it has against volatility in the real estate market that occurs if tenants default or properties lose value.

Since you own shares in a REIT, it is a type of equity investment. But it is different from individual stocks, stock mutual funds, or stock ETFs since a REIT must distribute at least 90% of its taxable income to its shareholders.

In addition, the return on a REIT is not necessarily correlated with the return on other equity investments. That's because real estate may respond differently to changes in the financial markets or the economy as a whole than other companies' stocks. REITs are correlated with inflation: Rising costs can be passed on to tenants, especially when leases are being renewed.

While a REIT has the potential to provide significant income, that income is taxed at a higher rate than applies to dividend income from most stocks. So many people choose to hold REIT investments in tax-deferred or Roth individual retirement accounts (IRAs).

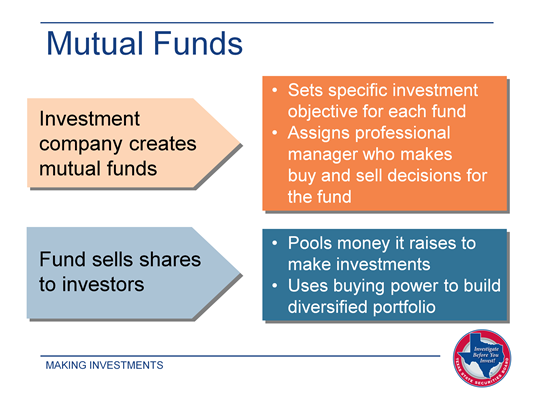

An investment company, also known as a mutual fund company, creates a group, or family, of mutual funds. Each fund has a specific investment objective, or goal, such as providing long-term growth, current income, or sometimes a combination of the two. These goals typically correspond with the kind of results people are looking for when they invest.

The fund company assigns a professional manager or team of managers to choose investments and make buy and sell decisions for the fund. Many investors appreciate having those decisions made for them, since picking and choosing among investments is one of the hardest parts of investing.

Once a fund is created, the sponsoring company sells shares to investors. Depending on the company, you may be able purchase shares online or by contacting a company representative. You may also acquire shares through sales people at banks and brokerage firms or by participating in an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan that includes the fund as one of its plan options.

The fund pools the money it raises from its shareholders to make its investments. The more attractive the fund is and the more shares it sells, the more money it has to build a broadly diversified portfolio — much larger and more diversified than you or any other individual investor could afford. That's another feature that makes mutual funds popular investments.

Because there are a number of fund companies that offer funds with similar objectives and make many of the same investments, one of the challenges you face is choosing a diversified portfolio of funds rather than buying several funds that invest in the same way.

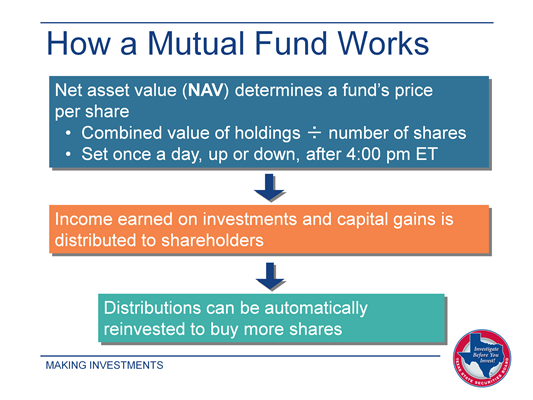

When you buy shares of a mutual fund, the price you pay is determined by the fund's net asset value (NAV). The NAV is calculated by dividing the combined market value of all the investments the fund owns, minus fees and expenses, by the number of shares investors own. The NAV fluctuates all the time as the prices of the underlying stocks or bonds and the number of shares change.

Unlike a stock, whose price moves up or down throughout the day as investors buy and sell shares, a fund's NAV changes just once a day, after the close of the stock trading day at 4:00 pm Eastern Time. All buy and sell orders for shares in the fund that are made during the day are filled at the new NAV.

Although the NAV doesn't usually change very much from day to day, it can rise or fall significantly over a longer period. If you sell shares when the price is higher than you paid to buy, you have a capital gain. If the price is lower, you have a capital loss.

The fund can also have income from capital gains, and from interest or dividends that are generated by its underlying investments. The fund, after subtracting expenses, passes along these earnings to its shareholders. One of the best things you can do with those earnings is to have them automatically reinvested to buy more shares in the fund.

Mutual funds have some distinctive features that distinguish them from individual securities like stocks and bonds.

Probably the most important is that mutual funds have diversified portfolios that help to manage investment risk. For example, a stock fund might own shares in hundreds of companies, domestic or international. Similarly, a stock fund might focus on one sector of the market — say, large-company stocks — or it might invest primarily in smaller, high-growth companies. A bond fund might own a particular category of bond, or a variety of corporate and government debt. Hybrid, or balanced, funds typically own a roughly 60-40 mix of stocks and bonds.

There are no guarantees that any investment, including mutual funds, will make a profit and a fund's holdings could lose value in a market downturn. However, it's often the case that diversification helps protect against severe losses you might suffer if you owned only a few stocks or bonds.

Another attractive feature of mutual funds is that it's easy to invest. Initial minimum investments are low and you can invest small amounts like $50 or $100 on a regular basis — or any time you want. Regular investing is good because it means new money is going into your account all the time.

Finally, a mutual fund company will buy back any shares you want to sell on the day you want to sell them, based on the NAV at the close of business. While you aren't guaranteed a profit, it is very easy to liquidate your shares.

Each mutual fund must provide a prospectus, or detailed written description of the fund. It's your best single source of information about a fund, and something you should review before you buy any fund.

Among the things the prospectus includes are:

- A statement of the fund's objective and the types of investments the fund manager makes to achieve that objective. If certain investments are not permitted, the prospectus will tell you that as well.

- The identity and experience of the fund's manager or management team. A change of managers sometimes prompts investors to leave a fund.

- The fund's performance history and the level of risk that investors face in putting money into the fund. It's important to remember that past performance doesn't guarantee future results. But what happened in the past does give you a sense of how vulnerable the fund was to market downturns and the type of environment in which it did well.

- A summary of all of the fees and expenses you face as an investor in the fund. The cost of a fund is one of the important factors to look at when comparing funds you are considering for purchase.

Mutual funds can be a good investment option for a number of reasons — professional management, built-in diversification, convenience of buying and selling — but they do carry fees. And the fees vary, not only from investment company to investment company, but from fund to fund within a single company.

All investors pay management and investment fees, which are reported as the fund's expense ratio in the prospectus, on the fund's website, and a range of financial news outlets. The fees are charged as a percentage of each investor's account value and subtracted before the fund's return is calculated and reported each day. An expense ratio can range from 0.10 or less to 2.75 or higher.

There may also be a fee for selling too quickly after you buy shares in some funds, exchange fees if you move money between funds, and other fees that may be possible to avoid. All fees are listed in the fund prospectus.

In addition, some fund sales people charge investors a sales charge, known as a load. It's generally a one-time charge figured as a percentage of the amount you invest. However, some loads are charged when you sell shares rather than at the time you buy. Not surprisingly, loads of any type are a significant drag on a mutual fund's performance. Whether or not a load applies is one of the things you'll want to check before you buy.

Paying attention to fees is important to smart investing. The lower the fees you pay for the funds in your portfolio, the more you'll boost your bottom line.

You can't avoid fees altogether. The fees on some types of funds are generally higher than the fees on other types. For example, fees on funds that invest in small companies tend to be higher than the fees of funds that invest in large, well-known companies. That's because identifying appropriate small companies takes more time and research.

Similarly, the fees on international funds that invest in countries around the world tend to be higher than fees on domestic funds that invest exclusively in US securities. However, it can be smart to own funds that invest in small companies and those that invest abroad to add diversification to your own portfolio.

The most striking differential, however, is the difference in fees charged by actively managed funds and index funds.

The objective of any actively managed fund is to provide a stronger return than the benchmark index for the type of investments it makes. For example, a fund that invests in large company stocks wants to outperform the S&P 500 Index, which tracks the combined performance of 500 large US company stocks. So the manager spends time choosing and trading investments. That increases the fund's costs, which are passed on to shareholders as fees.

An index fund, on the other hand, invests to replicate the performance of the index it tracks, not beat it. The investments it owns are the same as the ones in the index, so the fund doesn't have to pay a manager to choose investments. And there are few trading costs because the fund's portfolio changes only when the index company changes the companies in the index. The result is much lower fees.

What's more, index funds provide stronger returns than actively managed funds over the long term. Even though an actively managed fund might do significantly better than its benchmark in one or more years, it never does so consistently.

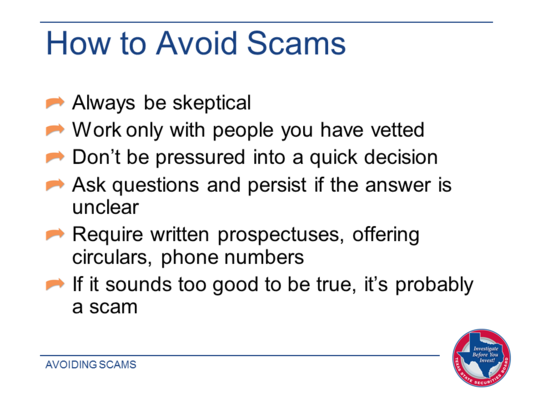

That exclamation point is there for a reason. Investing isn't a game, or entertainment, and risks can be substantial. Following our Investor's Checklist can help you avoid fraud.

✔ Receive complete information about the risks, obligations, and costs of any investment before you invest.

✔ Don't be rushed into an investment. Make a quick decision today and you may regret it for a lifetime.

✔ Contact the State Securities Board to obtain all regulatory information about firms and individuals handling your accounts.

✔ Receive copies of all completed account forms and agreements.

✔ Make sure you understand your account statements and check for accuracy.

✔ Make sure you can access your funds in a timely manner and receive information about any restrictions or limitations on access.

✔ Know precisely how much an investment is costing you in fees, commissions, or other changes.

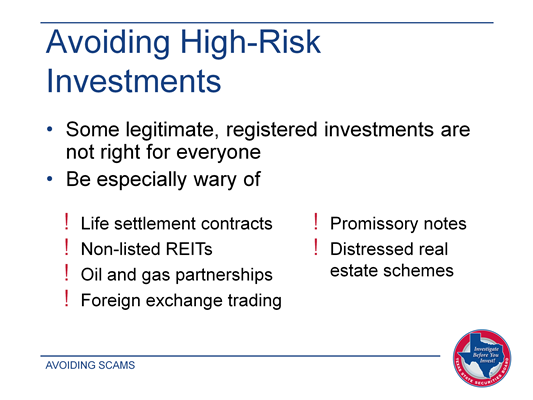

In the Avoiding Scams section of this presentation, you'll learn how to check whether an investment is registered and, just as important, whether the financial salesperson who is offering it to you is registered as well. Virtually all investment fraud involves unregistered securities and unregistered salespeople.

The other thing to keep in mind is that some legitimate investments may not be right for you. You may want to select only those investments that you can convert to cash quickly without owing a penalty, such as stocks, mutual funds, and ETFs.

Making investments is just part of being an investor. To achieve your goals, which are a primary reason to invest, you must evaluate your portfolio on a regular basis. That way you can be sure that the investments you've made are living up to your expectations. If they're not, you need to determine why and decide on a course of action, such as:

- Waiting out a market downturn

- Deciding to sell an investment that has consistently done worse than its peers

- Getting rid of an investment whose hidden fees and other costs put a drag on your return

- Revising your expectations because they were unrealistic

Checking regularly doesn't mean being obsessive about logging into your brokerage account every day and selling on every dip. In fact, that's a pretty reliable way to lose money.

Rather, you should plan to do a thorough review at least once a year, perhaps in January to get off to a good start, in April when you've evaluated your investment income for the previous year in preparing your taxes, or any time that works in your schedule.

Many investors, at one time or another, turn to a financial professional for help with their investment decisions. It's important to know the kind of help you need so you can choose the professional best qualified to provide it.

Investment advisers provide advice to help make investing decisions and may also manage investors' portfolios. Advisers earn a fee, usually a percentage of your account value.

Brokers, legally known as registered representatives, execute investing decisions, like buying and selling securities, on your behalf and may recommend securities. Brokers earn commissions on the transactions they execute.

Financial planners, sometimes called financial consultants or advisers, work individually or for local or nationwide firms. For a fee, a commission, or both, they provide financial planning and investment advice and offer ongoing evaluation of your investment strategy. Some, but not all, are licensed to sell insurance, annuities, and securities.

If you are considering working with an investment adviser or broker, the critical first step is to make sure the person is registered to do business in the State of Texas. The Texas State Securities Board's Investor Education site has a Background Check section on the home page. If he or she isn't registered, find someone else.

There is no one-stop background check for financial planners, who do not have to be registered with the state. But the planner may have earned an accreditation from a reputable organization.

Once you've confirmed that the professionals you're considering meet your standards, set up interviews with each of them.

To help you evaluate the professional help you may need, The Texas Family Guide to Personal Money Management contains a comprehensive financial adviser diagnostic that can help you make an informed decision about hiring a financial professional.

The diagnostic was created by the National Association of Financial Planners. It provides questions, checklists, and an answer key.

You can also use these valuable guidelines from financial writer Jason Zweig to help you prepare for interviews with financial professionals.

The bottom line is that you select the investment professional you'll work with based on

- His or her experience working with clients like you

- The way he or she is compensated

- His or her ability and willingness to answer your questions

It's also essential to evaluate how comfortable you are talking frankly to a professional you are considering. Compatibility and mutual respect are essential to a productive relationship.

As part of the initial conversation, be clear about your goals and expectations. And once you've made your choice, be prepared to participate in an ongoing dialogue.

As you make decisions about the types of investments you'll add to your portfolio, it makes sense to be guided by some basic investing principles.

Principles aren't rules you must follow: They're fundamentals that underlie how investing works. Understanding and applying these principles can help you make appropriate investment decisions.

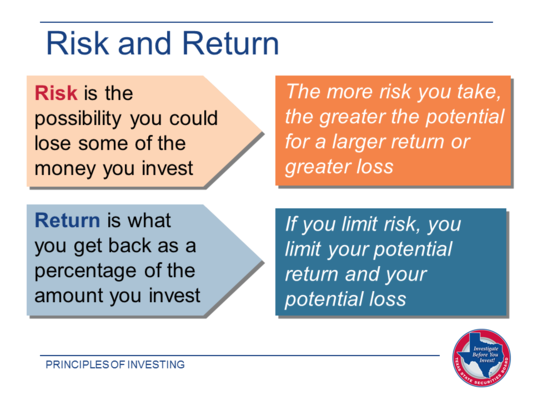

If you could sum up the essence of investing in just two words, it's about risk and return. Return is simply your gain or loss from investing. It's often reported as a percentage of the amount you invest. The higher your average annual return over time, the more likely you are to meet your financial goals.

Risk, however, can get in the way of a strong return. It's the potential for a negative return, or the possibility that you could lose money instead of making it. It's the possibility that you won't make as much as you need. Finally, risk is the likelihood that the value of any money you make will be undermined by inflation, reducing your buying power.

You can fight risk with two investment strategies — asset allocation and diversification. They don't guarantee success or protection from losses in a serious market downturn. But they should help you manage most investment risk while maintaining the potential for a strong return.

Using asset allocation and diversification, you spread your investment principal among several different types of investments, rather than putting all your eggs in one basket.

Understanding the risk / return relationship is essential to making rational investment decisions.

Why put your money at risk? The more risk you're willing to take, the greater the potential for having a substantial return. At the same time, if you take no risk, you'll have minimal, if any, return.

For example, if you put $1,000 in a bank CD paying 1% a year, your return for the year will be $10, or 1%. There's no risk that you'll have less than $1,000 in your account. But it will take almost 10 years to accumulate $100. On the other hand, if you bought shares of a stock, or equity, mutual fund providing a 6% average annual return, it would take just over 18 months to realize a $100 return.

The risk, of course, is that at any point in those 18 months your fund could be worth $800 instead of a $1,000, or even less if the stock market lost value.

If the thought of losing the $200 — or any money at all — is unacceptable to you, you may not be ready to invest. But keep in mind that it's entirely possible — though not guaranteed — that the mutual fund will regain its value over time and be worth substantially more than you paid for it.

You can find out more about the risk / return relationship in this article.

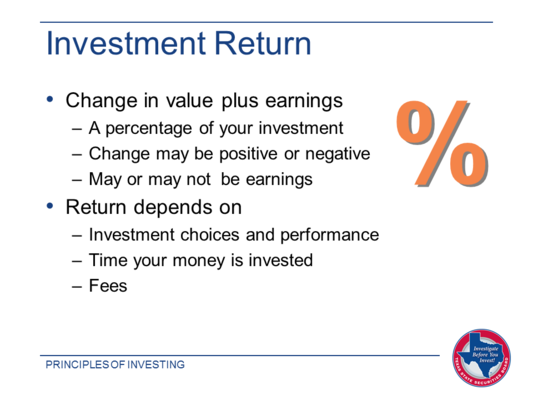

Investment return is based on two things: change in investment value plus any earnings the investment produces. For example, if you paid $20 a share for a stock selling for $21 a share a year later, and the company paid a $1 per share dividend, your return is a positive $2 a share, or + 10%.

In contrast, if the same stock were selling for $17 a share a year later and you received the same $1 dividend, your return would be a negative $2 a share, or – 10%.

Your overall return depends on three factors: how your investments perform, how long your money is invested, and the fees you pay to buy, own, and sell the investment.

Timing matters in two ways. If you'd sold the stock in the above example when it hit a low of $15 and you received just 50 cents in dividends before the sale, you would have lost $4.50, for a negative return of – 22%.

But if you'd held the stock for 10 years, and it had an average annualized return of 6%, your $20 investment would be worth almost $36. That's the result of the power of compounding.

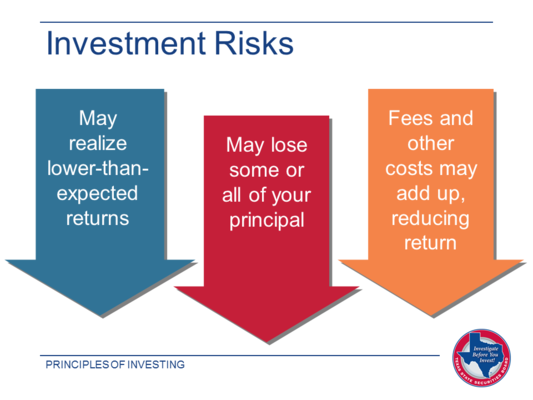

As you've seen in the previous slide, risk isn't necessarily as catastrophic as losing all your money in one terrible investment — though sadly, that can happen, especially if you're the victim of fraud.

The type of risk you're more likely to experience is having a smaller return on your investments than you expected. If the average real return on stock, for example, has averaged 6% over several years and you've used that figure to estimate your return, your plans can be disrupted if stock returns are essentially flat as they were in 2011.

There's also the risk you could lose money if you sell an investment when its price has dropped below the amount you paid to buy it. That happened to a lot of people in 2008 who sold because of their concern the market was going to decline even more steeply.

One of the things you need to understand about yourself is whether or not you'll be able to wait out a market downturn. If not, that may be a reason to stick to more conservative investments.

A third risk you face is that fees and other costs of investing can add up, especially if they are higher than average and reduce the return you expected.

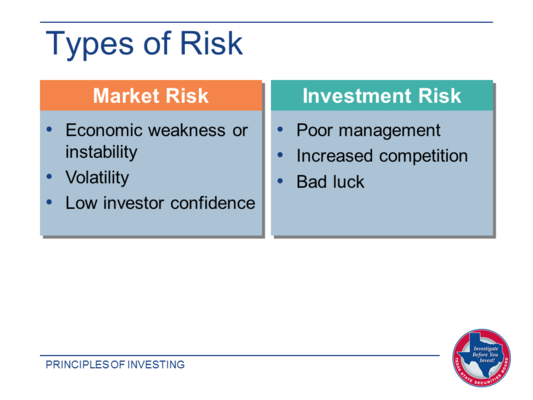

Most investment risk fits into one of two categories: market risk or investment risk.

Market risk refers to what's happening in the investment markets as a whole. If the economy is extraordinarily weak (as it was in 2008 and 2009), the markets can be extremely volatile — which means prices change dramatically over short periods of time. When that happens, investors tend to lose confidence in the markets and in investing in general. They stop making new investments and sell off the ones they own. This helps to create a severe downturn in most asset classes.

Investment risk, on the other hand, occurs when an individual investment, a specific market sector, and the mutual funds or ETFs that own shares of that investment or sector, lose value for one reason or another.

Investment risk may result from poor management that drives a stock price down. Some mistakes, like expanding too fast, can be too severe to allow the company — and its stock — to rebound. Sometimes a competitor introduces a product that runs away with the market, leaving a once-important product and its producer with a much lower market share or the risk of disappearing from the market altogether.

Similarly, bad luck, such as a natural disaster that interrupts the supply chain and depresses sales, may be enough to harm a company, reducing or wiping out its profits and leaving its investors with substantial losses.

While you need to confront investment risk, you don't have to be at its mercy. There are a number of strategies to help you manage risk without significantly reducing return.

Three of the most effective are:

- Asset allocation

- Diversification

- Controlling costs

Let's look at each of these more closely.

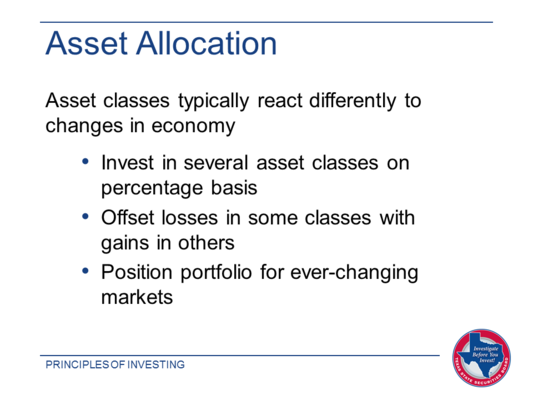

One key to managing market risk is to understand that different asset classes — equities, fixed income, cash equivalents, and real estate — react differently to what's happening in the economy at any given time.

You can take advantage of this phenomenon by investing in several different asset classes at the same time, dividing, or allocating, your portfolio among the classes on a percentage basis.

This strategy, called asset allocation, lets you offset losses in one class with gains in another, perhaps ending the year with an overall positive return. There's no guarantee that allocating will help you succeed, but failing to allocate is much more likely to produce losses — sometimes major ones.

Asset allocation also helps you position your portfolio to take advantage of the ever-changing markets — not by investing all your money in this year's hot class, but by having some investments in every class every year.

In this way, asset allocation decreases the risk of being overly concentrated in one asset class and experiencing major losses. For example, what would have happened if you'd owned only stocks in 2008, when the benchmark S&P 500 Index fell 37%?

The 10 years ended 2009 were the "lost decade" in stocks, with the S&P 500 posting an annualized return of -0.99%. In contrast, if you'd allocated your assets across stocks, fixed income, and a REIT, and rebalanced your portfolio every year, you would have earned a 4.2% annualized return — not enough to make you rich, but well ahead of large company stocks and inflation. Take a look at an allocation that produced that result.

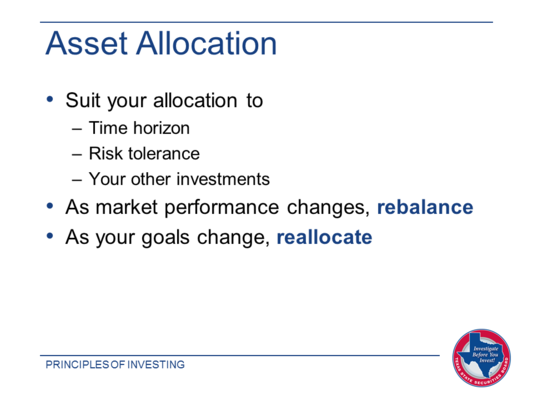

There's no single allocation that's right for everyone or that works perfectly in every market environment.

Rather, you choose an asset allocation to fit your

- Time horizon, or how long you have to achieve the goal for which you're investing

- Risk tolerance, or how much risk you are comfortable taking to meet an investment goal

- Your other investments or sources of income, which influence how much risk you can afford to take

As market performance affects the return on various asset classes, you rebalance your portfolio to bring your actual allocation back in line with the allocation you have chosen. Take a look at this article for more information.

Then, as your goals change, perhaps because you marry or divorce, have a child, or lose a spouse, you reallocate. For example, the closer you get to retirement, the more emphasis you may want to place on income-producing investments in your portfolio mix. That may mean gradually shifting from a portfolio heavy on equities to one with a higher percentage of fixed income.

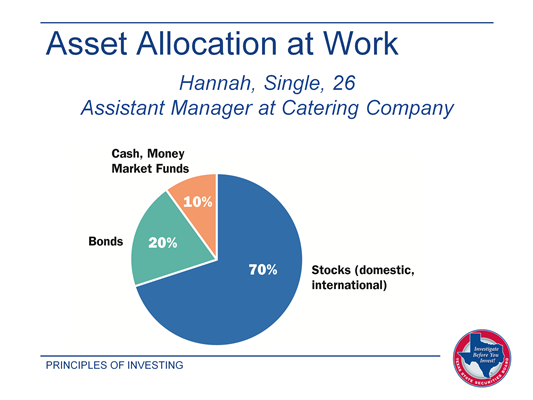

Hannah may be investing for a retirement that won’t begin for 40 years. Catering isn’t a particularly stable business, but she saves regularly when her finances allow it. Her minimal student loans are nearly paid off, and she has a small emergency savings account.

Allocating a large percentage to stocks, both domestic and international, and a smaller percentage to fixed income will probably result in a higher rate of return over the long haul than if the percentages were reversed. Hannah wants to keep things simple, so she invests in one fund indexed to the domestic stock market and a second one for international stock markets. Combined, these funds essentially own the world’s developed markets.

Investing in bonds is just as simple: there are funds that own domestic bonds of almost every type, such as government, corporate, and municipal. And because her job status, like most people’s, is subject to change, she wants quick access to cash through a money market mutual fund.

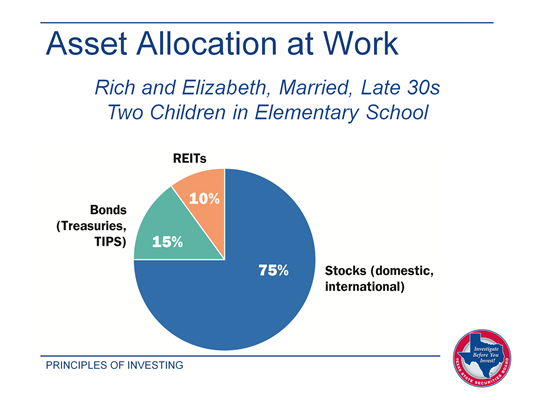

Rich is a firefighter – a job with a potentially lucrative pension – and Elizabeth is a mid-level employee at an established healthcare technology company. They figure they can ride out extreme fluctuations in the market as long as they have some ballast in their portfolio in the form of inflation-protected bonds and real estate investment trusts.

For Rich and Elizabeth, their job stability and earnings potential figure heavily in their investment decisions. While they are 10 or more years older than Hannah, they put a slightly larger percentage of their assets into stocks and a lower percentage into bonds.

The challenge for Rich and Elizabeth will be how they react to a sharp decline in the markets. If stocks, for example, decline by double-digits every year for several years, will they stay the course, or will they lock in their losses by selling in a panic? And if Rich doesn’t stay at his job long enough to qualify for a full pension, that may influence the couple’s thoughts about investment risk.

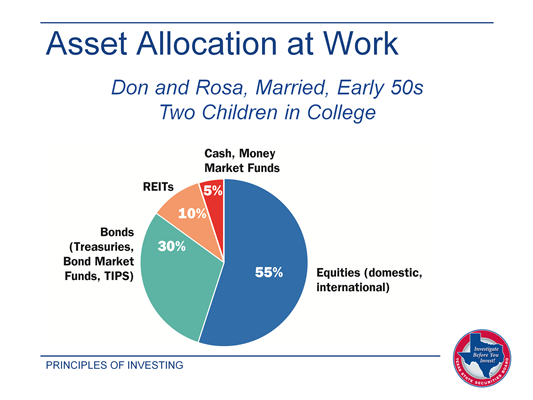

Don is an athletic director at a private school that offers a 403(b) retirement plan, not a pension, and Rosa is a manager at a “green building” construction company. Their challenge is continuing to save for retirement while paying college bills and making another 10 years of mortgage payments. Don, who didn’t finish college, is determined to pay as much of his children’s college costs as possible. He also wonders how his family would pay for ever-increasing healthcare costs – long-term and otherwise – an issue he experienced firsthand with his parents.

They may want to allocate a somewhat smaller percentage of their portfolio to equities and increase the percentage of bonds, TIPS, and real estate investment trusts. That way, if there’s a downturn in the market, they can draw on the fixed income rather than selling equities at a loss to get the money they need.

If one or both don’t retire for 15 or more years, however, they don’t want to abandon the growth potential of equities, which may make the difference in having adequate income in retirement and finding themselves short.

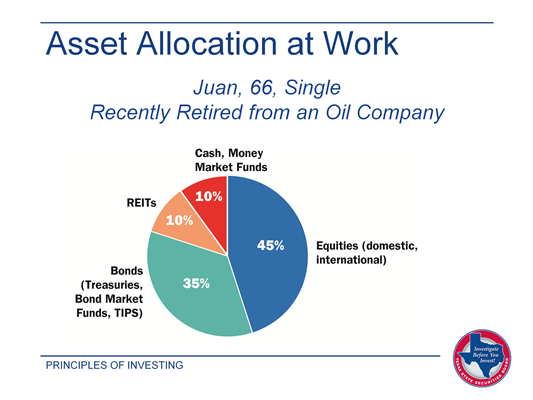

Juan has just started collecting a monthly annuity from his corporate pension. He has also just started drawing Social Security payments and has rolled over his 401(k) into an individual retirement account. He works part-time at an art supplies store, too, giving him four sources of income.

Juan's pension and Social Security payments are essentially fixed payments that will be made over his lifetime, so he could allocate the assets in his IRA any number of ways. He could take a relatively large amount of risk by investing most of his portfolio in equities.

Juan, however, grew up in an economically depressed region of Texas and he wants to minimize the chances of a big hit to part of his retirement funds. He also wants to keep a significant portion of his portfolio in cash – a money market account or a short-term bond fund – for easy access so he can travel and help out his nieces and nephews with college and other expenses.

However, if interest rates remain low, Juan won’t earn much on cash or short-term investments. If his health remains good, minimizing the chances of hefty healthcare costs, Juan may want to consider allocating a larger percentage to equities to seek the return that will help him live comfortably in retirement.

If allocating assets, and rebalancing and reallocating your portfolio seems complicated, or if you haven't ever rebalanced or reallocated the investment accounts you have, you may want to consider a target date fund.

Target date funds are goal-specific investments that reallocate their portfolios gradually: Over time, they shift from an emphasis on providing growth through equities to an emphasis on providing income from bonds and other fixed income investments. The pace and timing of the reallocation is known as a fund's glide path, and it varies based on the mutual fund company that offers the fund.

Every target date fund has a date in its title — ranging from 2015 to 2050 or 2055. You choose a fund whose date is closest to the year you plan to retire. Some employer-sponsored 403(b) plans offer these funds and you can choose them for an individual retirement account (IRA) or a taxable investment account.

Target date funds are also widely available in 529 college savings plans, where they are known as age-based tracks. There, instead of choosing by your target retirement date, you choose by the age of the student for whose educational expenses you are saving.

You can read more about target funds here or take a look at the way the allocation of four hypothetical funds with different target dates from the same fund company might vary.

While target date funds have lots of advantages, they also expose you to some potential risks, as all investments do.

Probably the most important is that target date funds don't guarantee their return, so it's possible you may not accumulate as much as you need by the time your target date arrives.

This risk isn't unique to target date funds. But because they're described as one-stop solutions for meeting specific investment goals and are managed by market professionals, they may seem a safer choice than other investments. Unfortunately, many investors found out otherwise in 2008, when some target date funds suffered serious losses in the market meltdown.

Another risk of target date funds is that they typically have higher fees than individual mutual funds. There are two reasons: The funds actually consist of other funds — they're funds of funds — each individual fund has its own fees plus an additional management fee.

What's more, target date funds offered by one company can vary significantly from those offered by another company in terms of glide path, risk levels, fees, and other factors. So you need to evaluate the specific fund you intend to buy, not just target date funds in general, before making a decision.

Despite their potential risks, though, target date funds are probably an investment alternative you'll want to consider.

Just as asset allocation helps you manage market risk, diversifying within each of the asset classes in your portfolio will help you manage investment risk.

When you diversify, you make several investments within an asset subclass. Asset subclasses tend to differ from each other in some important ways, though they all share the core characteristics of their class. For example, a large-company stock and a small-company stock are both equities. But they tend to increase in value at different rates, react differently to changes in the economy, and expose you to different levels of investment risk.

Similarly, bonds have different terms, different ratings, and different interest rates. They also have different issuers: the US Treasury, various cities and states, and corporations large and small.

In some ways, it may be easier to understand diversification by understanding what it's not:

- You're not diversified if you own six large-company stocks in the same sector of the economy

- You're not diversified if the only bonds you own are issued by the state in which you live or by the same US government agency

But your equity portfolio is diversified if you own three mutual funds, one tracking the S&P 500 Index of large-company US stocks, one tracking the Russell 2000 of small-company US stocks, and one tracking the MSCI-EAFE Index of major international companies. And your fixed income portfolio is diversified if you own some corporate bonds, some municipal bonds, and some Treasury bonds.

Here's an article that explores diversification in more detail.

In addition to market risk and investment risk, you have to consider what you pay to buy and own investments, since these costs add up and eat into your investment return.

It's not that investing should be free. It costs money to handle transactions. It costs mutual funds to manage their funds. And it costs brokers to maintain their offices and websites and provide research about investments you might consider.

Cost can be a particular problem, however, if you're paying more than necessary — including commissions, higher management costs, and redemption fees that you don't pay on other investments providing similar returns.

How do you avoid higher costs?

- As part of your investment research, always look at expense ratios and trading costs. Expense ratios are published in a fund's prospectus and on the fund company's website. Trading costs, or what it costs to buy and sell, are reported separately for stock and ETF transactions but not for mutual funds and bonds. These costs can be harder to find.

- Choose lower cost investments. Index funds and ETFs have lower expense ratios than actively managed funds. An index fund also has lower trading costs because its investments change only when the index that the fund is tracking changes — sometimes once a year or less.

- Choose lower cost investment accounts. You might open an online brokerage account, where commissions are often less than $10 a transaction. Many mutual fund companies will sell you shares in their funds directly, with no sales charges at all.

The reason that fees are so important to consider in making investment choices is that higher fees reduce your return.

Let's assume you own two mutual funds — Fund A, with an expense ratio of 2%, and Fund B, with an expense ratio of 0.5%. Let's also assume you have an account balance of $10,000 in each fund and each has an average return of 6% for the year before fees are subtracted.

Your fees on Fund A would be $200 (2% of $10,000), but your fees on Fund B would be only $50 (0.5% of $10,000). That's a spread of $150. If your account value were $100,000 in each fund, the difference would be ten times as significant, or a $1,500 difference in fees.

Despite what you might think, and what a high-priced fund manager might tell you, there is absolutely no evidence that higher-cost investments provide superior returns. In fact, the opposite is often true.

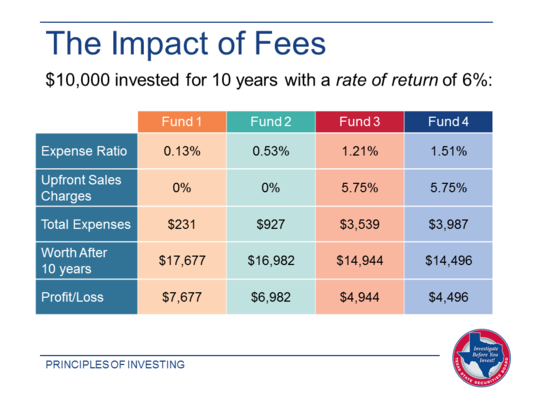

As you can see in this chart, the impact of fees on your investment return can be substantial.

Compare for example the gain of $7,677 earned on Fund 1 after total expenses of $231, to the gain of $4,944 earned on Fund 4 after expenses of $3,987. The lesson is clear: The higher a fund's expense ratio and the more you pay in sales charges, the smaller your return will be.

You can use the calculator on the Texas State Securities Board website to analyze the impact of expense ratios on mutual funds you may be considering as investments or funds you already own.

You have no control over many investment variables — the direction of the market, the rate of inflation, or how your investment earnings are taxed. But you do have control over one of the most critical variables — what buying and owning your investments costs. Every penny deducted for fees reduces your return. So comparing costs should be an important part of investigating before you invest.

Whether you're beginning your career or are nearing the end of your working life, it's the right time to think about investing for retirement. The primary way that investing for retirement differs from investing for other financial goals is that you get more help. That help comes in the form of tax-sheltered accounts that allow faster compounding and postpone taxes on your investment earnings until you retire and start withdrawing the money.

When you start thinking seriously about retirement, one of the first things to consider is what it will cost you to live comfortably in retirement. That gives you a basis for determining the income you'll need.

Some things will probably cost less once you retire: You won't be commuting. You won't need work clothes. Your mortgage may be paid off, or nearly so. Your children may have graduated from college and moved into homes of their own. There may be other expenses that will drop as well.

On the other hand, certain things will probably cost more. Health insurance and out-of-pocket healthcare costs are likely to be at the top of the list. Real estate taxes and property insurance may go up. Home maintenance costs continue. You may also want to spend more on travel, hobbies, or other things you've been waiting to do until you had more time. You may also want to get a small business off the ground.

And you'll still be spending money on food, clothing, and other necessities.

The consensus is that in retirement you'll need 75% to 100% your last working year's income to maintain your lifestyle after retirement. If you're single or the primary breadwinner, you should probably anticipate needing the higher percentage.

The reason is inflation: Your costs will increase over time, some probably faster than others. This means each year that you're retired you're likely to need more income than the year before.

There are potentially five primary sources of retirement income:

- A pension from a private company or public organization

- Social Security benefits

- Income from tax-sheltered retirement accounts to which you have contributed over the years. These include a 401(k), 457, or403(b) plan, which your employer makes available and to which you can defer salary, and an individual retirement account (IRA) to which you can contribute earned income

- Income from taxable investment accounts

- Income from a post-retirement job, either full-time or part-time

If you're concerned that you've gotten off to a late start in building your retirement assets, you might want to consider ways to catch up.

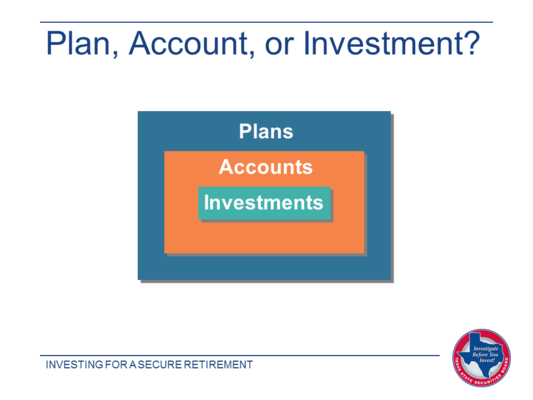

What makes a stock, bond, mutual fund, ETF, or cash equivalent a retirement investment?

The simple answer is that any investment becomes a retirement investment when you own it in a retirement account. While the exact same investment in any other account may eventually provide retirement income, it's not a retirement investment in the same way. A retirement account may, in turn, be part of a broader retirement plan, such as one sponsored by your employer.

For example, you can make retirement investments through an account in an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan, such as a 401(k), which is open to all eligible employees. If you participate, there's an account in your name in the plan. You defer salary to your account and can invest the money in any of the investments available through the plan — typically either mutual funds or annuity contracts.

Similarly, you may make investments through an IRA that you open with a bank, brokerage firm, or mutual fund company that serves as custodian of the account. The custodian keeps track of your account, sends you regular statements, and follows your instructions for investing your contributions.

In fact, the types of retirement investments you want to make — individual securities, mutual funds, or bank CDs — are an important factor in choosing where you open your IRA since you'll want a custodian that offers the range of investments you're considering for your retirement portfolio.

Since investments themselves don't distinguish a retirement account from a non-retirement account, what does? The answer is the way that earnings in the accounts — and sometimes the contributions made to them — are taxed.

In a taxable account, income tax is due on all earnings in the year you receive them. For example, if you collect $100 in interest payments in a year, that $100 is added to your taxable income when you file your return for that year. As a result, your tax bill goes up, based on the tax rate you pay on your earned income.

Any capital gains and qualified dividends are also taxed in the year you receive them, though at a lower, long-term capital gains tax rate. The primary exception is that interest on certain municipal bonds is tax free.

In contrast, with a tax-deferred retirement account, such as an IRA, income tax is not due on your investment earnings until you withdraw them from the account — typically over a period of years after you retire. And if contributions to the account were tax-deferred at the time you made them, as they would be with a 401(k) or similar account, tax is due on the full amount of every withdrawal, and not just on the earnings.

The tax rate that applies is again the rate you pay on ordinary income, though your rate in retirement may be lower than it was when you were working.

Two potential sources of retirement income, pensions and Social Security, are keyed to your lifetime of work.

While pensions are becoming less common, if you are eligible to receive a pension it can provide a steady source of income after you retire. Typically, the amount you'll receive in pension payments depends on the years you worked, the compensation you received, and other provisions that are specific to your company's plan. You should check with your HR department well in advance of your retirement date about the plan details, including payout options and other decisions you might have to make.

If you have worked and contributed to Social Security, you can expect to receive Social Security benefits when you retire. How much you receive will depend on a number of factors, such as the number of years you participated, the amount you paid in to Social Security, the age at which you start to collect, and if you continue to work but haven't yet reached full retirement age, how much you are earning.

As a rule, the longer you wait to begin collecting benefits, the higher your monthly payments. For people born between 1943 and 1954, 66 is considered full retirement age—the age when you can start to collect full benefits. Each year you wait up to age 70, the bigger your benefit will be. If you decide to take payment before the full retirement age, your benefit amount will be reduced proportionately.

To help you determine at what age you should start taking your Social Security benefits, check the calculator and other helpful information at www.socialsecurity.gov.

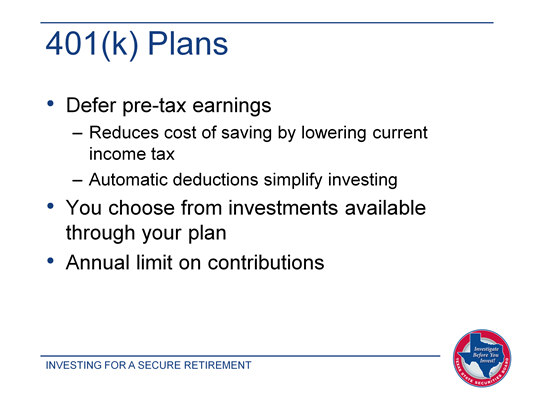

When you participate in a 401(k) plan, you defer pre-tax earnings to your account every pay period, typically by designating a percentage of what you earn. The deferred earnings aren't included in the gross income your employer reports to the IRS, which actually helps you save by reducing the income tax you owe for the year.

There is an annual cap on 401(k) contributions imposed by the federal government. That limit is $17,500 in 2014, plus $5,500 in catch-up contributions if you're 50 or older. You can contribute any amount up to that limit.

Since the salary deferral is handled automatically, making the contribution is easy. What may be harder is selecting the investments for your account. Most employers will provide a number of investment options, which are typically mutual funds or annuities, but may also include company stock. But it's generally your responsibility to select from among those choices to match your investment style, the level of risk you are comfortable taking, and the asset allocation strategy you've chosen for your portfolio.

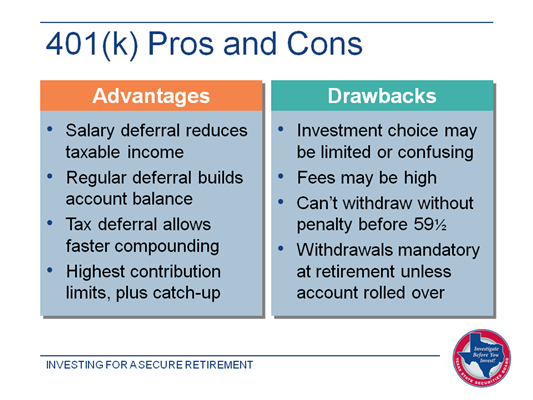

Should you be participating in your employer's 401(k) or similar plan? That's a decision you need to make, based on a careful consideration of both the advantages and potential drawbacks.

On the plus side are several things you're already aware of:

- Your contributions reduce your current taxable income and the income tax you owe

- Investing regularly helps you build your account balance

- Tax deferral on your contributions and earnings allows your savings to compound faster than they would in a taxable account since you don't have to withdraw money to pay taxes

In addition, 401(k) plans allow the highest contributions you're eligible to make to a retirement savings plan. That's a major selling point as well, if you can afford to contribute the maximum.

On the negative side, your investment choices may be limited, depending on what your employer-sponsored plan makes available, and the cost of owning the investments may be high in terms of fees and other charges. In addition, you can't withdraw the money until you are 59½ without paying a penalty, and taking withdrawals at the time you retire is mandatory, unless you roll over your account into an IRA.

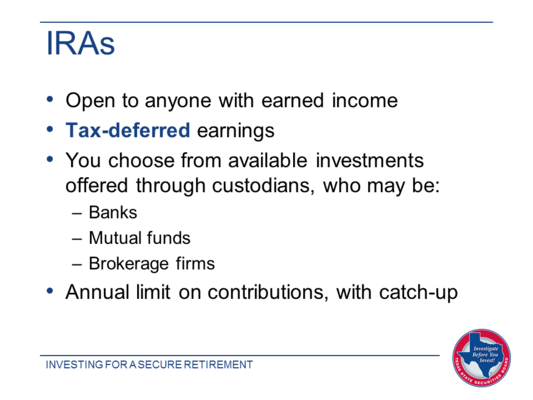

If you have earned income — as you do if you receive a salary, wages, commissions, or other income for work that you do — you can contribute to an individual retirement account, generally known as an IRA. What you may not realize is that you can contribute to an IRA in addition to participating in a 401(k), or other employer-sponsored plan, or you can choose an IRA instead of those plans.

With an IRA, earnings in your account are tax deferred, and no tax is due as those earnings compound.

You choose your own custodian — a bank, brokerage firm, mutual fund company, credit union, or other financial services company — and then select investments from among those available through the custodian. You can buy and sell as often as you like without tax consequences, though you will pay trading costs.

Like employer-sponsored plans, IRAs have an annual contribution limit: It is $5,500 in 2014, plus a $1,000 catch-up contribution if you are 50 or older.

You can read more about IRAs if you wish.

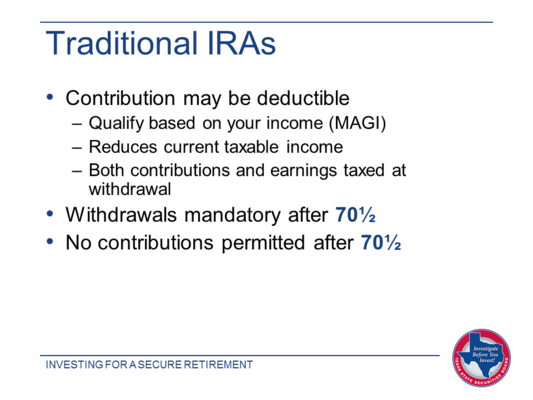

A traditional IRA is a tax-deferred IRA. Your earnings aren't taxed until you withdraw them from your account, usually after you retire. If you are at least 59½, there is no penalty for taking money out, even if you are still working.

You may qualify to deduct your contribution to an IRA based on your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). In 2014 you can deduct up to $5,500 if you file as a single taxpayer or as a head of household and your MAGI is less than $60,000. If your MAGI is between $60,000 and $70,000, you can deduct a gradually decreasing percentage, until your eligibility phases out with a MAGI over $70,000. If you’re married and file a joint return, you qualify for a full deduction up to a MAGI of $96,000, with gradually phased out eligibility until your MAGI reaches $116,000. Above that amount, you don’t qualify to deduct.

In years that you qualify, taking a deduction for your IRA contribution will reduce your taxable income. But remember, the contributions you deduct will be taxable, along with your IRA earnings, when you begin making withdrawals.

With a traditional IRA, you must begin to take required minimum distributions (RMDs) when you reach 70½, whether or not you need the money. You also must stop making IRA contributions at that age, even if you continue to earn income.

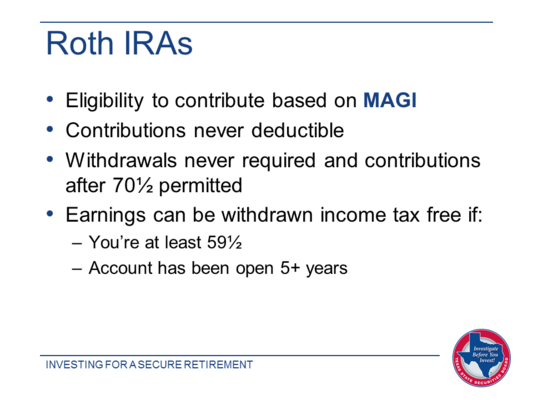

A Roth IRA has the same contribution limits and provides the same tax-deferred earnings as a traditional IRA. But the Roth also has several distinguishing features that may make it an attractive alternative.

The good news is that you are not required to start making withdrawals at 70½, as you are with a traditional IRA. You can also continue to contribute as long as you have earned income — even if you're 90.

Even better news is that you can withdraw your earnings tax free if you're at least 59½ and your account has been open at least five years. In addition, your contributions are not taxed at withdrawal either since you've already paid tax on them.

However, you do have to be eligible to contribute to a Roth IRA, based on your modified AGI. As a single taxpayer, you qualify to make a full contribution in 2014 if your MAGI is less than $114,000, and to make an increasingly smaller contribution until your MAGI reaches $129,000. The comparable limits if you're married and filing a join return are $181,000 and $191,000.

What's more, your contributions to a Roth IRA are never deductible. They're always made with after-tax income.

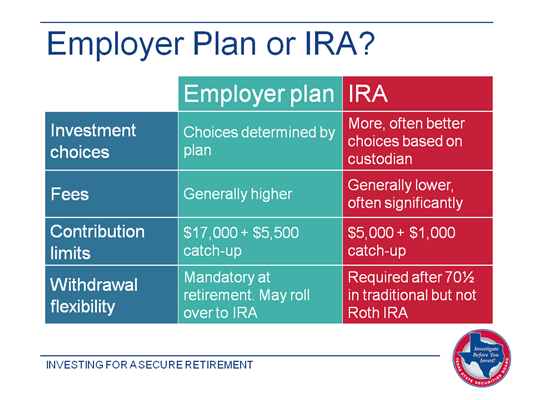

If you are eligible to participate in an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan, you have some choices in investing for retirement. You can choose to participate in the plan and also in an IRA, or you may consider forgoing the employer plan and simply establish an IRA, either traditional or Roth.

An IRA is likely to have more investment choices than a 401(k), 403(b), or 457, and IRA fees may be lower than you would pay in an employer's plan, sometimes significantly so. And while traditional IRAs require you to take withdrawals after you turn 70½, you may have more control over managing how you take those withdrawals than you do with a 401(k), 403(b), or 457.

On the other hand, employer-sponsored plans have much higher contribution limits, which allows you to build your retirement savings faster if you can afford to contribute more than the IRA cap. Investing is also probably easier with an employer-sponsored plan as well since all you need to do is sign up: Your contributions are automatically withheld from your pay and direct deposited into the investments you have chosen.

While you do have to set up an IRA with a custodian, once your account is established you can arrange to have money from your paycheck or checking account transferred directly into your IRA on a regular basis.

You may choose to contribute to a 401(k) or an IRA, or to both. You have the same options with a 403 (b) or a 457 plan. Whichever choice you make, you should not pass up this special opportunity to save for retirement with tax-deferred earnings.

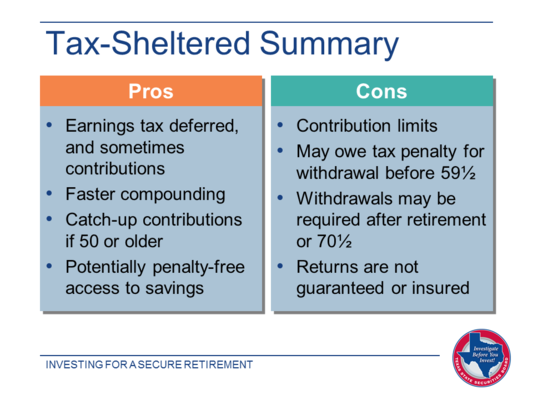

Tax-sheltered plans offer retirement savers some important benefits:

- Your retirement account earnings and sometimes the contributions you make to those accounts are tax deferred.

- Your account value can compound faster because of the tax deferral, which may mean the potential for larger account balances.

- You can make extra contributions after you turn 50, when you can perhaps afford to save more.

- There's no penalty for early withdrawals if you use the money for certain allowable expenses, such as paying college tuitions, covering medical bills, and making a down payment on a first home.

If you use a tax-sheltered plan, however, you should be aware that there are some strings attached:

- There are annual contribution caps, which means you can enjoy the benefits of tax deferral only on a limited amount of money.

- You may owe a penalty for withdrawals before you turn 59½, though there are some exceptions.

- You may be required to make withdrawals at retirement or after you turn 70½.

- Your returns aren't guaranteed or insured, so even if you invest regularly you may end up with less money than you need to live comfortably in retirement.

You spend most of your working life building your retirement accounts, so it can be hard to make the transition from saving and investing to spending the money you have accumulated. But when that time comes, you want to be ready. Just as you followed a strategy to invest for retirement, you'll also need a plan for withdrawing from your accounts to live comfortably while ensuring your money lasts your lifetime. The place to start is estimating your retirement income needs.

When you begin to take retirement account withdrawals to supplement your pension and any money you earn from continuing employment, you should plan to have enough combined income to cover your key expenses.

The cost of maintaining your household is likely to take the biggest bite out of your retirement income. Some of these expenses are more or less fixed, so it's easy to budget for them but harder to economize. Typical expenses include mortgage or rent payments, car payments, basic telephone service, utilities, property insurance, and taxes.

Anything that's not essential is discretionary — though people define "essential" in different ways. There's a very fine line between what you need and what would be nice to have in retirement. You (and your family) should develop a spending plan that reflects the distinctions you've made.

The cost of medical care and insurance is "the elephant in the room." Since most people have higher health care expenses as they get older, and since health care costs increase at a rate that tends to outstrip inflation, you may spend much more for health care costs than you anticipate.

You should anticipate increasing your withdrawal amount each year by a percentage equal to the rate of inflation.

With withdrawals from your retirement accounts, there is one strategy that you should pursue: Wait as long as you can. There are a number of reasons for postponing withdrawals. Perhaps most important is that the longer your assets are tax-deferred, the greater the potential they have for growth.

In addition, if you're younger than 59½, the amount you withdraw is considered an early withdrawal and will be subject to a 10% tax penalty — and that's on top of the income tax that's due. This double whammy could significantly reduce the actual amount you have to spend.

Keep in mind, however, that there are exceptions to the penalty rule for early withdrawals, including using the money for certain compelling reasons, such as covering medical bills, paying college tuition, and putting a down payment on a first home. You may also avoid the penalty by setting up a plan for regular annual withdrawals over at least a five-year time frame or until you turn 59½, whichever period is shorter.

Even if you have an excellent reason for an early withdrawal, however, the result is the same: You deplete your retirement savings, which you'll need to live a comfortable retirement. And the closer you are to retiring when you start to withdraw, the more difficult it will be to rebuild your account balance.

That means you face the very real possibility of running out of money in your lifetime — something that many people worry about.

Rather than taking early withdrawals or retiring at the first opportunity, you may want to consider postponing retirement for a few years. It's one of the most effective ways to ensure greater financial security as you grow older.

For one thing, the longer you work, the larger your pension is likely to be. That's because you and the state will have contributed more to TRS, which will increase the amount of your annuity.

You'll also be able to contribute more to your tax-deferred accounts, including your employer-sponsored plan and IRA. As little as five more years of additional contributions can make a dramatic difference in your bottom line.

Say, for example, that in the year you turned 55 your IRA account value was $100,000. If you stayed on the job, maxed out your annual IRA contribution, and added $500 a month for the next five years — until you turned 60 — your new account value, assuming an annualized return of 6%, would be $169,944 — an increase of more than two-thirds.

And, of course, the longer you wait to start taking money out, the larger the undisturbed balance on which future earnings can accumulate.

Before you begin to withdraw from your retirement accounts, you should determine the amount you'll need and decide which accounts you'll tap first.

You generally start to take distributions from your 401(k) or similar plan at retirement, unless you can arrange to postpone them or you move those assets to a rollover IRA. If you can get along without the 401(k) money, and if you want more flexibility in choosing investments and managing withdrawals, a rollover is something you may want to consider.

If your distributions from employer-sponsored plan aren't large enough to cover your retirement needs, you can supplement these distributions with the interest and dividends from your taxable investments, which ideally you've been reinvesting all along.

You might also consider part-time work if you're eager — or willing — to supplement your income and reduce the amount your draw down from your retirement accounts.